Love in Translation: A Review of 'A Lover’s Discourse'

A book review of Xiaolu Guo’s 'A Lover’s Discourse': what it means to love across cultures.

I'm Monica, and I navigate life as a multi-country expat, surrounded by books and writing. My mind is modeled by the 5 languages I speak (almost) daily.

Millennial Monica is my newsletter about what it’s like to live a multicultural life and not lose your true self along the way. Interested in reading more of my work?

“I wanted to be a woman in the world, or really, a woman of the world - I wanted to equip myself with an intellectual mind so that I could enter a foreign land and not be lost in it.”

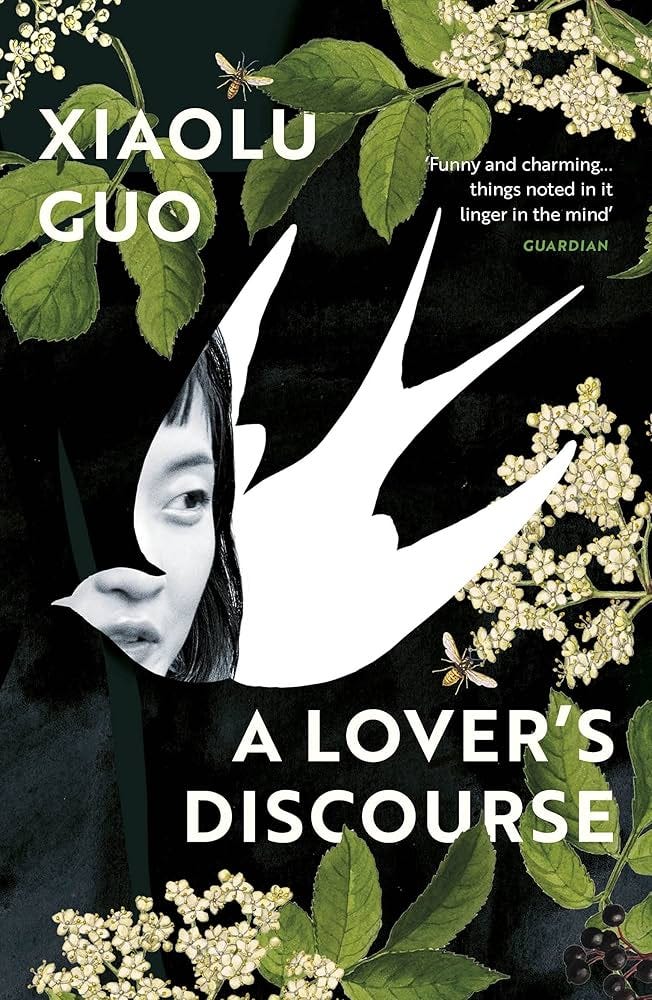

I usually don’t buy hardcover books. They feel too formal and hard to get into. I prefer paperbacks, with their flexible covers that I can bend and feel better in between my hands as I read. But the hardcover of ‘A Lover’s Discourse’, painted with black, deep green and white doves, caught my attention on my local library shelf. The short vignette-style chapters I browsed through convinced me to pick it up quickly enough.

The narrative is fractured, poetic and constantly goes back to the dissonance of cultural differences between two people falling in love. It is a novel with a clear narrative line and even a surprising third act, but it reads like a series of reflections — on language, belonging, and the inevitable loneliness that sometimes hides even in romantic intimacy.

Otherness

The narrator, a young Chinese woman who’d just landed in London to start a PhD in film anthropology, meets a German-Australian man. Their love story is shaped and moulded by the cultural differences between them.

He prefers to live on a boat, she prefers the stable earth — she’s come from afar and been on the move for long already.

He is nostalgic about camping in Australia, while she craves the dense noise of a city.

He is casual and self-assured in a way that only someone who has always felt they belong can be. She watches herself constantly — as a woman, as an immigrant, as a foreigner navigating a language and culture that is not her own.

“I saw a poster with the word Brexit. I didn't know what it meant. I hadn't read any English newspapers since I arrived. I checked the word in my pocket Chinese-English dictionary. Oddly, it was not there.”

“English nights were long, and they didn't belong to the non-pub-going people. Nor did they belong to foreigners, especially those friendless and familyless foreigners. What were we supposed to do at night in our rented rooms, if we didn't drink or watch sports?”

This sense of otherness permeates the entire novel. The narrator does not just feel like an outsider in London; she feels like an outsider in her own relationship. Even in moments of intimacy, there’s a persistent gap between them — the unspoken awareness that he will never truly understand her dislocation, her longing for context, her deep need for roots in a place that feels rootless.

“Something about his way of speaking suggested to me that in his Universe I was a secondary citizen.”

“But I knew that even if one day I could master a foreign language — one of the major European languages — I would still not become a primary citizen of the West.”

“I was surrounded by white people. White Europeans, talking and laughing. I thought, even though I speak English, and I can read and write in English, still, I feel monolingual.”

When she goes deeper into details about her former life in China, we get to see up close a different society, we are offered the contrast to her present life in England. As a migrant from communist Eastern Europe myself, this book spoke to me and probably to others too, making her story universal. The common thread of the cultural shift of all migrants who moved West from communist parts of the world.

“She was not a tiger mother like other Chinese women who were strict with their children. But she was unaffectionate. She never enjoyed her life. ‘To live is just to suffer. Nothing good comes out of it.’ That was her daily motto. For her, life was only about dealing with practical matters. Anything non-practical for her amounted to stupidity. And I was very impractical.”

“There must be some positive aspects to one's parents passing away. Now I was free to be insane or stupid. And I had to see my current life as one of the positive things I had gained from losing my former Chinese life.”

“And when my mother died, my attachment to China began to die too.”

Fernwech

The chapter called ‘Fernwech’ could very well have given the title of the book too. The German word Fernwech talks about the ache to be somewhere far away, a yearning for distant places not yet known. While her boyfriend seems to embody this restless, romantic wanderlust — living on a boat, dreaming of desert road trips — the narrator experiences fernweh differently. For her, it is a more existential ache, a yearning for a place that can hold her completely, a place where she doesn't have to translate herself to be understood.

“It's funny we Germans speak of weh, pain, while the English for Fernwech is wanderlust or travellust. I feel more pain than lust.”

But as much as she felt free to be insane or stupid and build her new life the way she pleased, the narrator also felt the pull of her motherland. And the author doesn’t waste the golden occasion to do a play on words again:

“‘In this case, I prefer the German - Vaterland, rather than Motherland’, I said to you, before I headed off to Heathrow. For me, I rather think China is my Fatherland. ‘But in our Vaterland we still speak Muttersprache’, you responded, walking me to the train station.”

Power dynamics

Her fernwech is quenched when she travels to China to document the painters who copy famous European paintings. Despite the hot and humid weather, her cells know she is home. The original home, the birthplace one will always have, no matter how far one migrates in the world.

“This was something I didn't have in England. The vitality. It was an essential thing I missed when I was away from my native country. What is more important, I asked myself: the vitality of Eastern life, or the order of Western civilization?”

The reason she travels to China is a fascinating one: to document on film a village of painters who specialized in reproductions of the famous European masterpieces, from the Mona Lisa to Van Gogh portraits. She films the artists while painting and mentions their technique, using Chinese black ink instead of the European oil-based colors.

The theme is layered. We all know the stereotype of the Chinese copying everything, including entire cities. But the author challenges the idea of originality as the marker of value. If someone paints an exact replica of a Van Gogh painting, does that make the artwork meaningless, or does it hold its own value? Do the Chinese copies have any value in and of themselves?

Expanding the theme to her relationship, I perceived a subtle power dynamic between her boyfriend, coming from a Western background, and her, a Chinese woman. Just as Western countries control the discourse on “original” vs. “copied” art, the boyfriend often dominates the relationship dynamic, dismissing her needs or perspectives.

Discomfort

As the book progressed, I found myself increasingly unsettled by the boyfriend’s behavior. While he is not overtly cruel, he has a persistent dismissive attitude toward her. At least, that’s how she perceives it, as she narrates their story. He cannot seem to grasp the emotional weight of her migration. Honestly, I kept waiting for her to break up with him. There were moments when I hoped she would walk away, not because I wanted their relationship to fail but because I wanted her to claim space for herself that didn’t involve constantly bending around someone else’s comfort.

But perhaps this discomfort is part of what Guo wants us to sit with. Love, especially love across cultures, is not a tidy fusion of difference. It is a negotiation, sometimes tender, sometimes painful, between people who carry with them vastly different ideas of home, belonging, and selfhood.

“There had been this feeling of wu yu — wordlessness and loss of language — which had enveloped me.”

Throughout the book, the prose moves just like thought: fluid, intuitive, fragmentary. This structure — short, elliptical chapters that often end in the middle of a thought — mirrors the very process of cultural translation. Meaning is always partial, incomplete, refracted through language and memory.

Beyond the narrative of the love story, the poetic aspect of the book manages to dig deep into what it feels like to be a migrant and to create a whole new life far away from one’s place of birth, among foreign people and different customs.

Verdict: Highly recommended! ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

If you enjoyed this piece, the best way to support me is to share it ❤️, either on social media or restack it 🔄 here on Substack. It's an easy click for you, and it helps me reach more readers. Thank you!

What a well-written review of a book I’m sure would resonate with many of us who have lived in a culture foreign to us. Thanks for sharing this, Monica. I hope our local library has a copy!

This has taken me back to when I read the book, which I also bought in hardback because the cover was beautiful. I was nodding along to your observations (that boyfriend was a bit obnoxious, let's be honest) and you've reminded me how much I enjoyed this novel and Guo's reflections on language. I recently recommended another of Guo's books to a colleague and I'll make sure to point her to this post as well : )